Background: Taxes, Boycotts, and the Rise of Public Opinion

The roots of the American Revolution lie in British policies that taxed the colonies without granting them representation in Parliament. After the French and Indian War left Britain deeply in debt, Parliament passed a series of tax acts to raise revenue from the colonies. Each new law sparked protests, boycotts, and public gatherings that helped colonists see themselves as part of a shared political community.

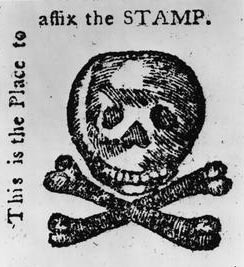

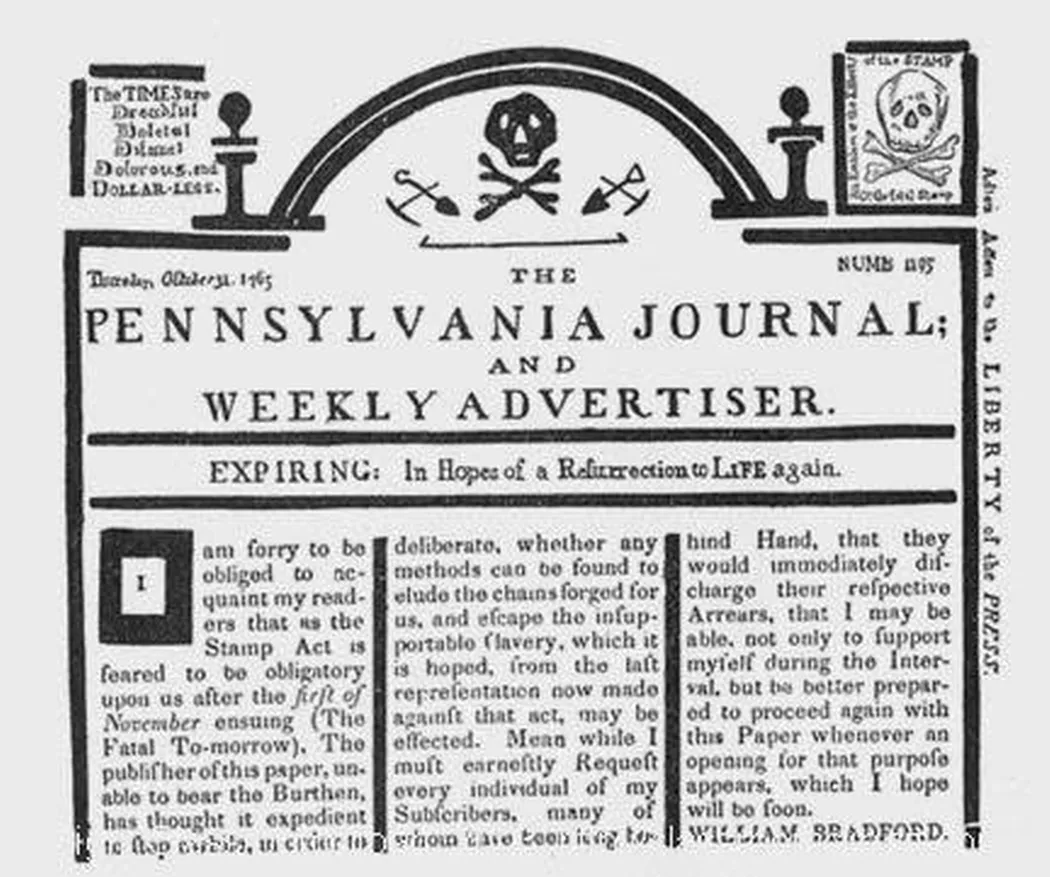

The Sugar Act of 1764 taxed molasses and other imports, threatening colonial merchants and rum producers. The Stamp Act of 1765 required colonists to purchase stamps for printed materials, including newspapers, legal documents, and playing cards. This tax hit printers, lawyers, and ordinary people who needed paper for daily business. Colonists organized Stamp Act Congresses, burned stamped paper, and forced stamp distributors to resign ("American Revolution"; Gould). The Townshend Acts of 1767 taxed goods such as tea, glass, and paint. These acts also allowed British officials to search colonial homes and ships, which many colonists saw as a violation of their rights.

When Britain repealed the Townshend Acts but kept the tax on tea, colonists responded with the Boston Tea Party in 1773. Parliament then passed the Intolerable Acts, which closed Boston Harbor, restricted Massachusetts self-government, and allowed British soldiers to be quartered in colonists' homes. These measures united the colonies in anger. As the historian Eliga H. Gould notes, the Intolerable Acts convinced many moderate colonists that Britain aimed to crush all colonial liberties ("The Revolutionary War"; Gould).

Boycotts became a powerful tool of resistance. Colonists refused to buy British goods, and merchants signed non-importation agreements. Women organized spinning bees to produce homespun cloth instead of importing British textiles. These boycotts did more than hurt British trade. They created public rituals that brought neighbors together and reinforced the principle of "no taxation without representation." When people gathered to hear readings of protests or attended sermons condemning British policies, they participated in a growing political culture that crossed class and regional lines (Morgan).

Print played a central role in spreading these ideas. Newspapers printed resolutions from town meetings, reprinted speeches, and listed the names of merchants who broke boycotts. Broadsides were posted in public squares and taverns. Ministers referenced British abuses in sermons, and those sermons were then printed and circulated. This combination of spoken and printed communication meant that colonists in distant towns could learn about events in Boston or Philadelphia within days or weeks.

The slogan "no taxation without representation" became a unifying idea. It expressed a belief that colonists, as British subjects, deserved the same rights as people living in England. Parliament's refusal to grant colonial representation convinced many that Britain saw the colonies as sources of revenue rather than as equal partners. This sense of injustice fueled a shared identity that crossed boundaries of region, occupation, and wealth. Public opinion, shaped by print and public gatherings, transformed individual grievances into a collective movement ("The American Revolution"; Gould; Morgan).