Thomas Paine's Common Sense: Plain Words, Urgent Change

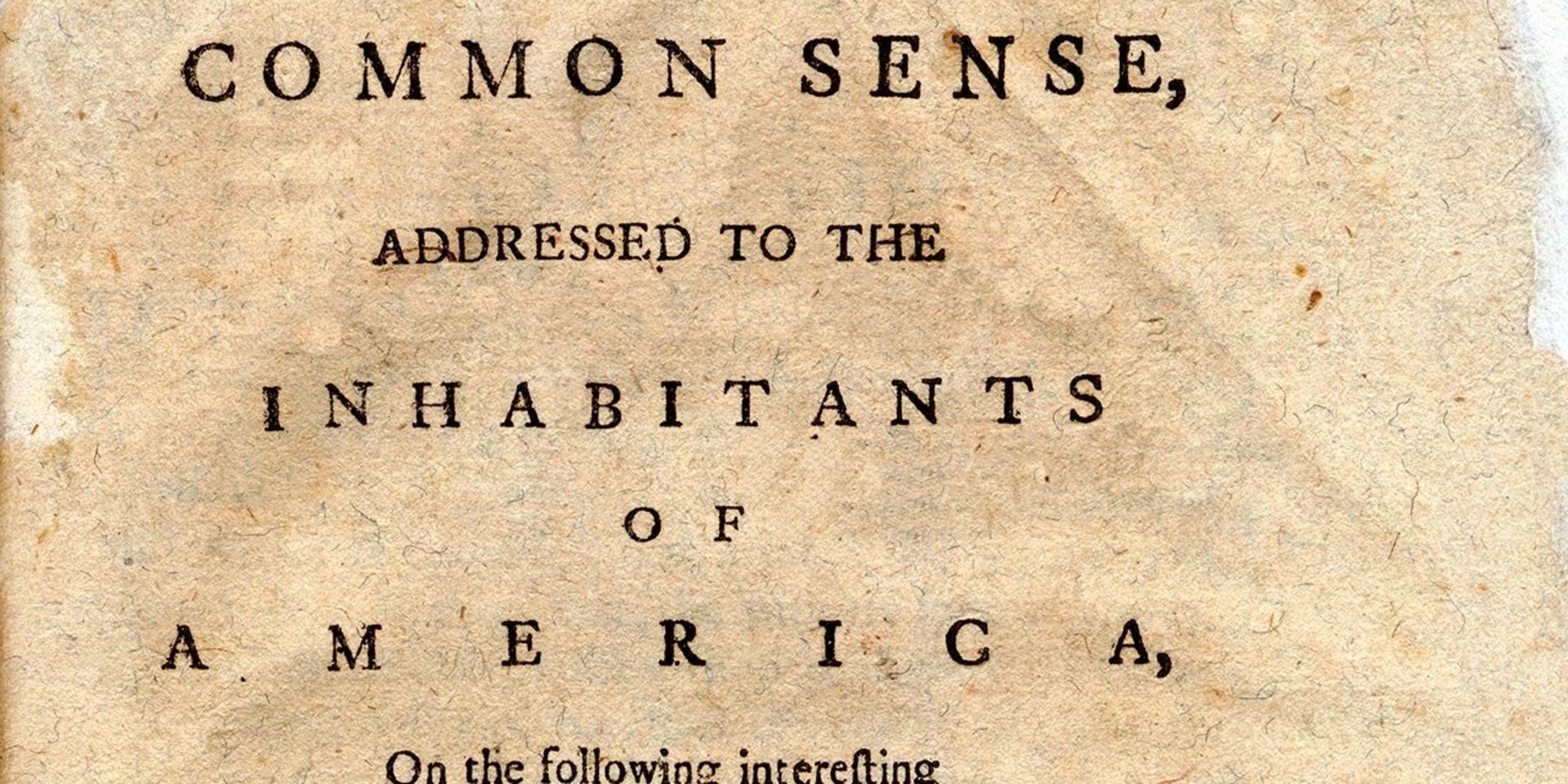

In January 1776, a forty-seven-page pamphlet appeared in Philadelphia. It was called Common Sense, and it changed the conversation about independence. The author, Thomas Paine, was a recent immigrant from England who had worked as a corset maker, tax collector, and writer. He had no formal political power and no famous name. Yet his pamphlet sold more than 100,000 copies in its first three months and eventually reached an estimated 500,000 readers in a population of about 2.5 million. Proportionally, that would be like a book selling tens of millions of copies today (Kiger; "Common Sense By Thomas Paine").

What made Common Sense so powerful was Paine's style. He wrote in plain English, avoiding the formal legal language and Latin phrases that marked most political writing. He used short sentences, everyday examples, and direct address. Reading Common Sense felt like listening to a friend explain why independence made sense. Paine spoke to ordinary colonists, not just to educated elites. He assumed his readers were capable of understanding political arguments and making their own decisions (Kiger; "Common Sense By Thomas Paine").

The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind.

Paine's central argument attacked the idea of monarchy itself. He argued that kings were not chosen by God but were descendants of bandits and conquerors. He called hereditary rule absurd and unjust. This was a radical claim. Many colonists still respected King George III even as they opposed Parliament. Paine rejected that distinction. He argued that the king was just as guilty as Parliament and that independence was the only reasonable course ("Common Sense By Thomas Paine"; Kiger).

Paine also made practical arguments. He claimed that America did not need Britain for trade or protection. The colonies could govern themselves, build their own navy, and form alliances with France and other European powers. He framed independence not as a distant dream but as an urgent necessity. Delay, he argued, would only lead to more suffering. Paine wrote, "The blood of the slain, the weeping voice of nature cries, 'Tis time to part'" ("Common Sense By Thomas Paine"; Kiger).

Common Sense appealed to shared values. Paine used biblical references that resonated with religious colonists. He invoked ideals of liberty, equality, and self-government that crossed regional and class lines. He addressed economic interests, telling merchants and farmers that independence would benefit them. He spoke to emotions, describing British rule as cruel and unnatural. This combination of moral, practical, and emotional arguments reached a wide audience ("Common Sense By Thomas Paine"; Kiger).

The pamphlet's success shows how print culture had prepared the ground. By 1776, colonists were used to reading and discussing political pamphlets. They had participated in boycotts, attended town meetings, and debated British policies in taverns and homes. Common Sense entered this existing conversation and pushed it in a new direction. Before Paine, many colonists hoped for reconciliation with Britain. After Common Sense, independence seemed not just possible but inevitable ("Common Sense By Thomas Paine"; Kiger).

Paine's plain style was itself a political statement. By writing in language that anyone could understand, he asserted that ordinary people had the right and ability to judge political questions. He rejected the idea that only elites should discuss government. This democratic approach matched his argument for self-government. If colonists could read and decide for themselves, they could also govern themselves. Common Sense thus became both an argument for independence and a demonstration of the principles it defended ("Common Sense By Thomas Paine"; Kiger).