Pamphlets: How Do They Affect Public Opinion?

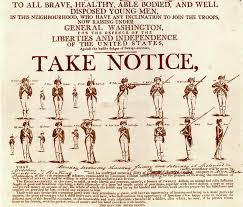

Pamphlets were the social media of the Revolutionary era. They were cheap to print, easy to carry, and quick to reproduce. A pamphlet might cost a few pennies or be given away for free. Printers could set type for a short text in a day and produce hundreds of copies on hand-operated presses. Once a pamphlet appeared in Boston or Philadelphia, other printers in smaller towns reprinted it, sometimes with added commentary or local context ("The Revolutionary War"; Warner; Morgan).

Pamphlets covered every kind of argument. Some offered careful reasoning about constitutional rights. Others used sharp humor, personal attacks, or religious language to stir emotion. Authors ranged from educated elites like John Adams and John Dickinson to anonymous writers who hid behind pseudonyms. This diversity meant that colonists encountered multiple voices and perspectives, which helped political ideas spread beyond any single group or class (Warner).

Pamphlets gave ordinary people the tools to debate politics as if they were members of Parliament.

The format encouraged debate. A writer might publish a pamphlet attacking British policy, and another writer would respond with a counter-pamphlet. Readers discussed these arguments in taverns, town meetings, and around dinner tables. Because pamphlets were portable, a single copy might pass through dozens of hands. Someone who could not afford to buy a pamphlet might hear it read aloud at a public gathering or borrow it from a neighbor (Warner; Morgan).

Some pamphlets became famous. John Dickinson's Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania argued that Parliament had no right to tax the colonies for revenue. His careful, respectful tone appealed to moderates who valued legal arguments. Other writers, like Samuel Adams, used fiery language to call for resistance. These different styles reached different audiences, but all contributed to a broader conversation about colonial rights and British power (Warner).

Pamphlets also crossed regional boundaries. A text written in Massachusetts might be reprinted in Virginia, and a debate that began in one colony could continue in another. This created a sense of unity, as colonists saw that people in distant places shared their concerns. The medium itself encouraged this unity. Because pamphlets were cheap and easy to reproduce, ideas did not stay locked in one city or social class. They moved quickly, spreading arguments and emotions across the colonies (Warner; Morgan).

Printers played a key role. Many printers, like Benjamin Franklin, were also political actors. They chose which pamphlets to print, which essays to publish in their newspapers, and which voices to amplify. Printers faced risks. British officials could arrest them for sedition, and loyalist mobs could destroy their presses. But many printers saw themselves as defenders of free expression and colonial rights. Their willingness to print controversial material ensured that dissenting ideas reached the public (Warner).

Pamphlet culture shows that the Revolution succeeded in part because it was a conversation. Ideas moved from print to speech and back to print. Colonists did not just read arguments. They talked about them, argued over them, and used them to shape their own understanding of events. This participatory culture helped transform unrest into a movement. When Thomas Paine's Common Sense appeared in 1776, it built on this existing culture and took it further, using plain language to argue that independence was not just justified but necessary (Kiger).