Paul Revere's Engraving: Image as Persuasion

On March 5, 1770, British soldiers fired into a crowd in Boston, killing five colonists. The event became known as the Boston Massacre. Within three weeks, Paul Revere produced an engraving titled The Bloody Massacre Perpetrated in King-Street, Boston on March 5th 1770. This image did more than record an event. It shaped how colonists understood who was to blame and what the killings meant ("Paul Revere's Engraving").

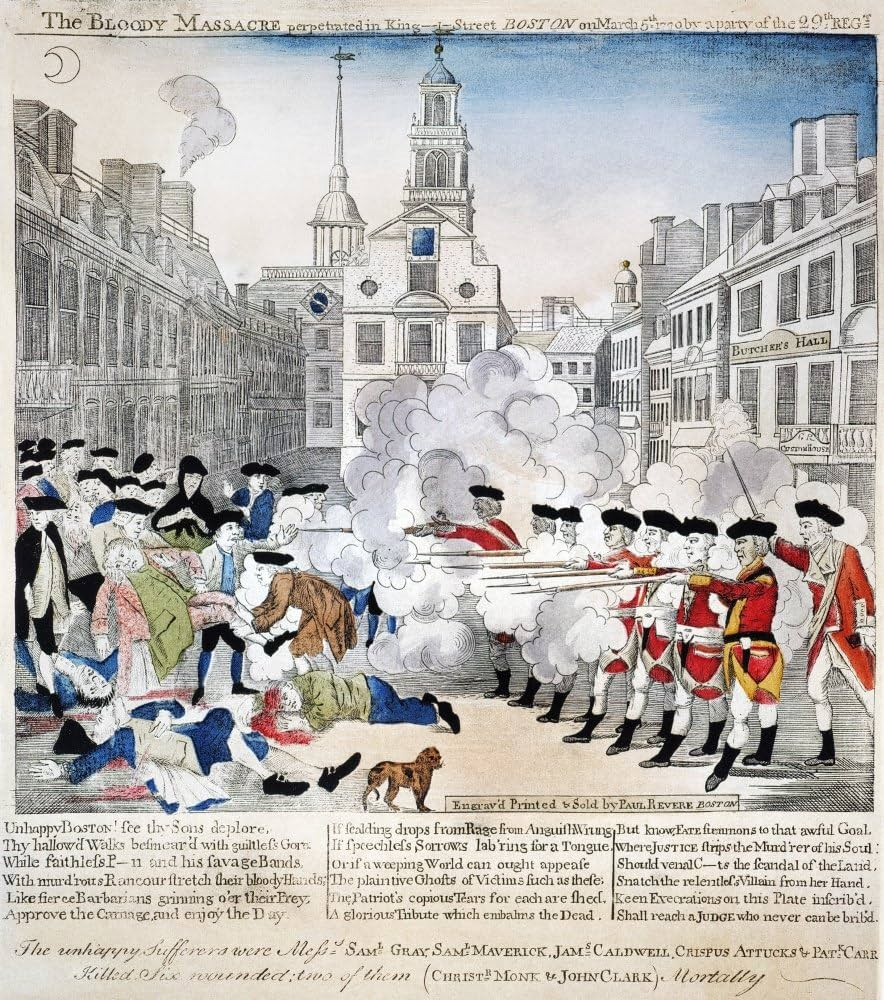

Revere adapted his engraving from a sketch by Henry Pelham, a Boston artist. Pelham accused Revere of stealing his work, but Revere's version reached a wider audience because he printed and sold it quickly. The engraving shows British soldiers standing in a neat line, muskets raised, with smoke rising from their guns. An officer stands behind them, his hand raised as if giving the order to fire. The colonists are shown as defenseless victims, some falling to the ground. A distressed woman appears in the background. Even a dog in the foreground remains calm, staring out at the viewer, symbolizing loyalty and suggesting that the violence was one-sided and unprovoked ("Paul Revere's Engraving").

Revere included readable details that added to the moral message. The building on the left is labeled "Butcher's Hall," linking the soldiers to butchery. The Custom House, a symbol of British taxation, is clearly marked. The sky above is illustrated in a way that seems to cast light on the British "atrocity." These choices created a simple story in which British soldiers committed murder while colonists stood helpless. The image did not match the more chaotic reality described in court testimony, which mentioned snow on the ground and confusion about who gave orders. But accuracy was not the point. The engraving's purpose was persuasion ("Paul Revere's Engraving").

One significant detail involves Crispus Attucks, an African American merchant sailor who had escaped from slavery more than twenty years earlier and was among those killed. Attucks is visible in the lower left-hand corner of Revere's engraving. However, in many other copies of this print that circulated later, he was not portrayed as African American. This erasure or alteration reflects how propaganda often simplifies history to serve a political message. By removing or downplaying Attucks's identity, later versions made the narrative of white colonial victimhood clearer and avoided complicating the revolutionary story with uncomfortable questions about race and slavery ("Paul Revere's Engraving"; Parkinson).

Revere also included other visual elements that shaped the narrative. The British soldiers' faces are drawn with sharp and angular features, making them appear menacing, while the colonists have softer, more innocent features. The soldiers look like they are enjoying the violence, particularly the soldier at the far end. The colonists, who were mostly laborers and working people, are dressed as gentlemen, elevating their status to make viewers sympathize with them more. There even appears to be a sniper in the window beneath the "Butcher's Hall" sign, adding to the sense of calculated British aggression ("Paul Revere's Engraving").

The engraving spread quickly. Copies were sold in Boston and reprinted in other colonies. People who had never been to Boston could see the image and feel outrage. The visual format made the message immediate and emotional in a way that written descriptions could not match. The image required no special education to understand. Anyone could look at it and grasp the central claim that British soldiers had killed innocent colonists in cold blood ("Paul Revere's Engraving").

Produced just three weeks after the Boston Massacre, Revere's engraving was probably the most effective piece of war propaganda in American history. By choosing specific details, arranging figures in a certain way, and labeling key elements, Revere created a version of the event that served the colonial cause. The image traveled far beyond Boston, shaping public opinion in places where people had no other source of information about the incident. It became a symbol of British tyranny and colonial victimhood. As propaganda, it succeeded because it was simple, emotional, and easy to reproduce. This kind of visual persuasion helped build the broader revolutionary movement by giving colonists concrete images of British injustice ("Paul Revere's Engraving"; "The Revolutionary War").